“Happiness is not found in a fast-paced life, but rather in living in harmony with our planet”. This statement, which was made at the VII Congreso Edificios Energía Casi Nulo (VII Nearly Zero-Energy Building Conference), sums up the philosophy of the long and hard road toward sustainability, where society’s commitment is essential for saving both the planet and ourselves.

We already have the tools we need to build a new model that allows to us to address climate change as well as meet the Sustainable Development Goals, which include the fight against energy poverty. In order to achieve all of this, the decarbonisation of buildings is a must.

Ética Arquitectura told us that “existing buildings are responsible for approximately 40% of the CO2 emissions in the European Union. Reducing the energy needs of buildings will result in less CO2 emissions in the atmosphere, which is why the decarbonisation of buildings is essential.”

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

The basics of an energy-efficient building

New European regulations will help to achieve this goal by setting out the minimum guidelines that the sector must follow. In 2012, the EU released guidelines for the reduction of emissions, and the transposition of those guidelines should now be in effect in the legislation of all member states. In practical terms, this means that from 2021 onwards, all new buildings must be Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings.

Many who are committed to achieving sustainability and working in the sector in Spain are already one step ahead, constructing sustainable buildings and going beyond what the minimum standards require.

What is a Nearly Zero-Energy Building?

The European guidelines define a Nearly-Zero Energy Building as one that has a high level of energy efficiency when it is being used in a normal way. The small amount of energy that it does use must come mostly from renewable energy sources produced in the building’s immediate environment. This requires passive systems that reduce energy demands and active systems that meet the air conditioning, hot water, and ventilation needs of the building with renewable energy on site.

Although the latest update to the Spanish Código Técnico de Edificación (Technical Code for Building) has laid out the minimum acceptable conditions, these regulations are open to interpretation, meaning that many have opted for the Passivhaus certification, which is also used in other European cities such as France and Brussels. Passivhaus has more stringent standards based on a functional definition and an energy quantification common to all countries that allows for very specific quantification of a high energy efficiency standard.

As Passivhaus consultant Oliver Style explains, “the Passivhaus system is very interesting because first, it limits energy demands and then, in the second stage, it looks at how to generate renewable energy in situ”.

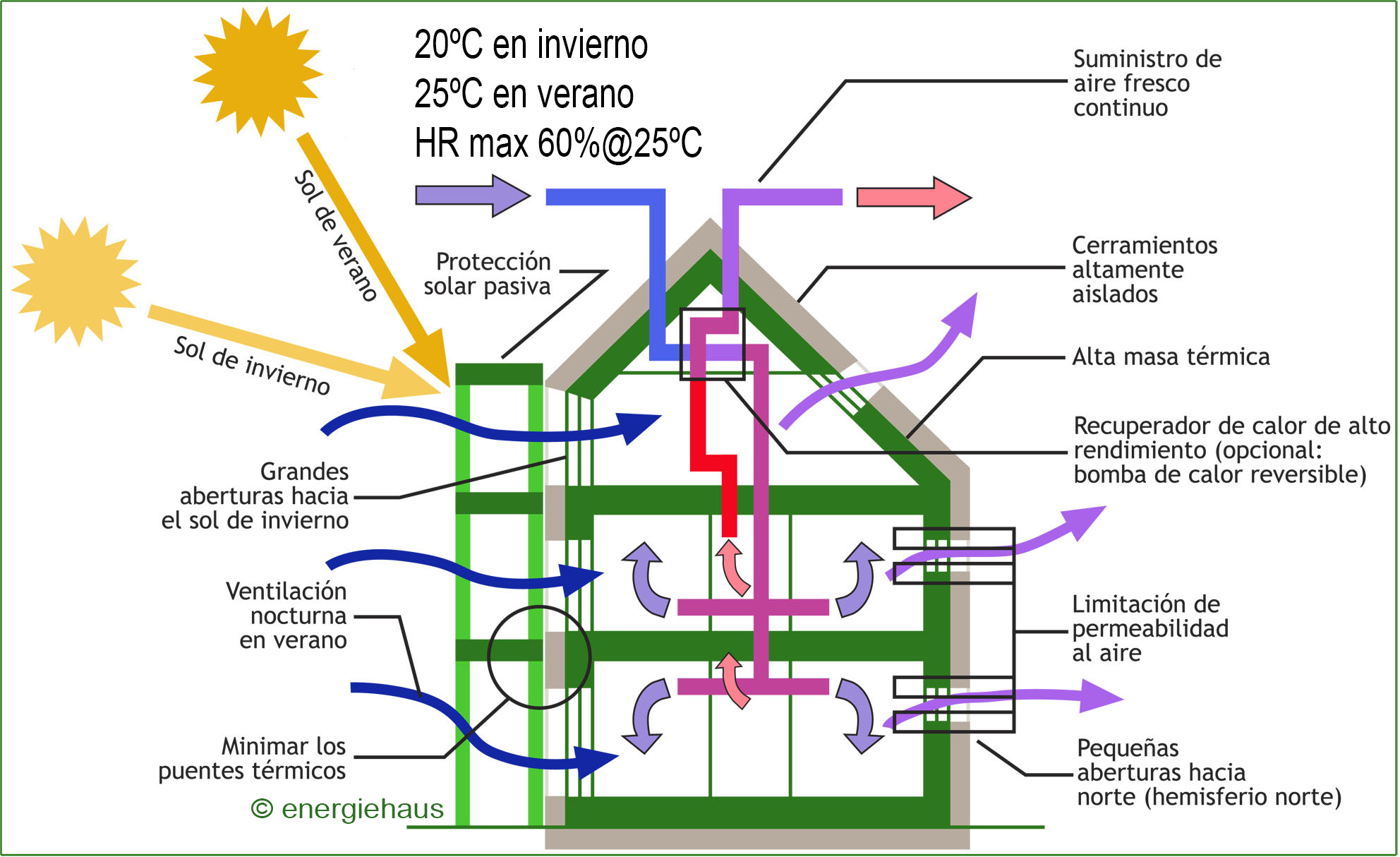

It also provides a higher level of comfort and indoor air quality which, as Energiehaus Arquitectos founder Micheel Wassouf points out, “make it a home that is capable of maintaining a level of comfort indoors on both the coldest and hottest days of the year by providing the necessary energy for heating or cooling using an air flow stream that is already essential for the ventilation of our homes”.

The key to achieving the objectives of a Nearly Zero-Energy Building

Experts in sustainable building are very clear about this. For architect Iñaki del Prim “Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings are a reality, they are necessary, and it is our moral obligation to build them. I think the best way to do so is by using passive strategies. Standards like Passivhaus will result in this type of building”.

So, what is the secret to building in this way? For Ética Arquitectura, it’s about “passive design”. This means that “thanks to the resources from architecture itself and the constraints resulting from the building’s site and location, we can make sure that the building heats itself, that it doesn’t overheat in summer, and that the energy we use for climate control doesn’t get lost the moment we turn off these systems”.

We are talking about buildings that need very little energy. As Oliver Style explains, this can be achieved by creating a thermal envelope. “A well-designed thermal envelope loses very little energy. It’s like having a coat that wraps around the whole building, making sure the heat stays in during the winter and that it stays out during the summer.”

These are buildings that both protect the planet and are more comfortable for their inhabitants. “If we think about a building as a machine whose energy needs we need to reduce, we are going to get it all wrong. The building is made for people and the goal must always be creating comfortable spaces that don’t negatively affect people’s health,” Style says.

According to Micheel Wassouf, the six basics for Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings are thermal insulation, good windows, thermal bridge control, controlled ventilation, solar power, and an airtight seal. Finsa is one of the first companies to have a material certified specifically for creating such seals- superPan Tech P5.

The materials used in Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings

The materials used are just as important as the design. Although an energy-efficient and comfortable building can be made from any material, there are certain choices that are more suited to this type of construction. One of these is timber.

Oliver Style explains that wood has a lower thermal conductivity than other materials: 0.13 compared to concrete’s 2.5 and steel’s 50. “If we use a wooden framework rather one made of reinforced concrete or metal, we are using a material that, thanks to its thermal properties, carries less heat, meaning that it’s easier to reduce heat loss,” he says.

These properties and others make this material perfect for efficient structures. Iñaki del Prim says that timber “has insulation properties, increased hydrothermal regulation, is sustainable, and is very versatile. It doesn’t limit the project in any way. You can design whatever you like using timber, as long as it’s well thought-out”.

Experts agree that using timber has advantages for both construction and the environment throughout the entire lifecycle. It is sustainable while the building is in use, as well as during the design, manufacture, construction, and even demolition phases. Gerardo Wadel, founding member of Societat Orgánica, says that, when each stage is analysed closely, from material extraction right up until the final stage of waste management following demolition, “materials can make up two-thirds of three-quarters of the impact”.

He says that that’s why timber is important, because “when it comes to carbon, the tree itself needs carbon to grow, meaning that there is a level of absorption that gives you a material that doesn’t produce it during the manufacturing stage. In addition, it helps other materials meaning the carbon production during construction is very low or almost non-existent. It’s renewable, meaning that the tree you cut down, with all that stored carbon, has been replaced by other trees. This is measured and certified, and when you buy it, you can be sure of this. It’s reusable. It can be reused for another project or it can be recycled to make new boards. It is constantly kept in the technical cycle: it’s either being reused or recycled, but it never becomes waste”.

.

Objective: energy rehabilitation

How quantifiable are these energy savings? It’s been shown that the design and construction of Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings can result in a 90% reduction in energy demands compared to a conventional building, and that percentage is proportional to the reduction in CO2 emissions.

These parameters can be applied to new buildings as well as those undergoing comprehensive rehabilitation. Energiehaus has applied these figures to rehabilitation using refurbishments that they are working on. “Using that 90% reduction, we calculated what would happen if all the homes in Barcelona were refurbished using the Passivhaus standard, and we would be able to turn off a whole nuclear power plant. It would [save] the equivalent of what a plant like the one in Ascó generates annually. This is just an example that shows the potential of this approach,” says Wassouf.

Is it possible to undertake a comprehensive rehabilitation project when so many residential buildings already exist? Four out of five buildings are inefficient from an energy standpoint, and many homes built before 1979 even lack thermal insulation.

Experts agree that, from a construction and a financial standpoint, it is in fact possible; however, there is a huge barrier, and it’s the social one. Buildings aren’t empty shells – they house people. Logistically, this is the greatest difficulty. Nevertheless, it is something that must be considered. “We will construct very few new buildings that will be nearly zero-energy when in use and carbon neutral during the other phases of their lifecycle. In ten years, this will add up to about 5% of building stock. The other 95% will be under older codes and this is what we really have to address with rehabilitation. Energy rehabilitation that adheres to very strict standards makes up a very small part of current rehabilitation projects,” explains Gerardo Wadel.

He knows that this is a task of “titanic proportions”, but the opportunity to attempt it is there, especially because current rehabilitations are usually functional and aesthetic, but don’t deal with energy.

He says that that’s why we must take action and that “we must intervene in rehabilitations as much as possible. Will it be enough? No, it won’t be, but we shouldn’t just stay silent about where we live while we wait for the building to be rehabilitated. Maybe you’ve got very little timber or insulation in your home, or maybe renewable energy isn’t being used, or the facilities are old. An organised, conscientious, and motivated community can work wonders”.

Future challenges: positive energy buildings

Where previously the goal was to build Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings, now this is just the starting point. The EU has said that by 2030 all newly constructed buildings must have a carbon neutral lifecycle and in 2050 building stock should be neutral.

That’s why we must head in the right direction and fast, so that we can deal with the new challenge of the future, which Ética Arquitectura explains is “the construction of positive energy buildings, meaning those that produce more energy than they use”.