Rocío Pina and Carmelo Rodríguez, together with David Pérez, are the heart of ENORME Studio. Recently arrived in Milan, where they designed Finsa’s concept for the FuoriSalone Astral Bodies, and showed their work at Rossana Orlandi’s gallery, we spoke to them about their approach to architecture and design.

How was ENORME Studio born?

Carmelo Rodríguez: We started 12 years ago as students – 8 friends. We have had various names and various formations. ENORME Studio is their evolution. More than anything it came out of the great desire to do things, which is something that defines the studio right now. We get very excited about projects – each one is a challenge and that passion for each project that we carry out is still alive.

Rocío Pina: We immediately had the urge to create our own projects and we wanted to change a lot of things that we were very tired of. We started in 2006/2007, when the real estate bubble burst, and we took a very radical position when it came to those architectural excesses, like understanding a city in a more shared way, the idea of working as a team…a much more sustainable approach to architecture which very much countered what was done before.

What is so good about working in a team?

CR: Any design work is a very collaborative type of work. The idea of the designer as a solitary creative genius, which isn’t real, has been maintained for years. The team is very important, and that’s why we always talk about collaborative architecture because there’s no other way to do architecture and design. There are certain hierarchies and tasks in which some of us have more expertise than others, but it’s important to take care of this design group ecosystem that allows you to complete a project or pursue a common objective.

Your residential projects are based on the importance of flexibility. Will lack of space be a problem in the future? How did you end up creating the mobile systems solution Living Big?

RP: Lack of space is a problem in the present, especially in cities with a high population density. We are fighting against this phenomenon every day. But sociological models and family types have changed: people that live alone, single-parent families, working from home etc. It’s not just about the lack of space, but rather a series of situations for which traditional residences do not have the answer. The Living Big project worked on that: on one hand, the lack of space, and on the other, the need for homes to adjust and transform more easily over the course of the day. Each room must have the capacity to allow for multiple living situations.

CR: It’s also about understanding that furniture is becoming increasingly important in the domestic environment and that it can’t be dissociated from the space in general. It’s not a question of constructing a container and then putting furniture on top of it, but rather working in a more connected way. This type of thing is not going to be built using bricks or heavy elements, it’s going to be built using much more mechanised systems which have to do with wood or aluminium. There has been a radical change to the way we understand our homes and we are implementing this right now.

You talk about returning the city to the citizens through initiatives whose designs encourage participation. How do you see the city of the future?

CR: One of the biggest challenges of those of us who work in the construction of the city is generating amongst the general public a pedagogy and culture of design related to urban spaces, domestic spaces etc. Until we create the contexts in which we can talk about the city and generate new imaginaries within them, it’s going to be hard for us to have better cities. The city of the future, the city of the citizens, happens in meeting places where we can chat, debate, and learn how to make the city together.

RP: It’s a setting in which you are conscious, as a citizen, that the city, the streets you walk on, are not something separate from you but rather something that depends on you a little, and that may also require you to act. Even though there are more and more platforms created by institutions that allow us to form part of that transformation, there is still a lot to do.

Speaking of the future, where is the future of Enorme Studio headed? What projects do you have in the works?

CR: The future of Enorme will take three distinct paths and that enriches the day-to-day of our work. These three lines of work include projects of a certain scope that we can develop in parallel. The first is related to experimentation surrounding flexible domestic and work spaces. We want to expand it and change the scale, to go beyond that almost individual question and system prototype which could serve a lot more people.

RP: It’s about rethinking how we live collectively in a block of flats: not looking at the home as a single unit but rather how could it be a transformable block of flats, something like co-living.

CR: The second line of work is about educational spaces. We are working on a project with the RESAD (La Real Escuela Superior de Arte Dramático de Madrid or the Royal School for Dramatic Arts) in which we are building and designing spaces with members of the community. Students, teachers, and maintenance staff participated in the workshops, among others. We are interested in the question of working with the community, which doesn’t have to be educational, and how we build their work, recreational, and other spaces with them in a collaborative way.

The third line of work is related to our latest project, Astral Bodies, because it is about “extraordinary spaces”. Right now we are preparing scenery for the Mañana conference at IFEMA (the trade fair institution of Madrid), which will be the first event that does not produce waste or elements to be recycled because everything will be reused. It will be constructed using the same element – picnic tables – which will then be functional in the fair environment. We are interested in all these “extraordinary spaces” that go above and beyond and that come up with new ways of understanding a certain context.

We can see a wide range of projects in your portfolio: furniture design, domestic and urban spaces, ephemeral architecture etc. If you had to choose just one, which would you choose?

RP: I don’t like dividing the projects up by category because I think they have a lot more in common: the ingredients, the way they are worked on etc. I believe that it’s more about diversity. What does change is the context, but the approaches are very similar: the critical spirit, the challenging of situations that each project presents us with, the idea that the participating agents make it their own etc. Our projects always end up having a lot of people involved and a strong sense of ownership.

What would be your dream project?

RP: Right now, we would like to make the idea of taking our solutions for domestic spaces to another level with a co-living space a reality, and to understand how these new family groups translate to a block of flats. We are in talks to develop it with various agents.

CR: In the field of educational spaces, we would like to be able to apply all our know-how to a project from the beginning, a school for example , using methodologies that we have used on a small scale in the construction of a whole building.

You teach for the Masters of Ephemeral Architecture at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, the IED (European Institute of Design), the ESNE (the University of Design in Madrid), the University of Umea (Sweden)…What idea of design do you transmit to your students? And what do you learn from them?

RP: One think that we have learned from working in a team is to encourage the students to trust their ideas. Teaching consists of empowering them so that they can firm up their own paths, their own ideas, including those that you don’t like, finding the way to help them do it better by using their own instincts, which is something that we have been searching for since the beginning.

We also try to transmit the idea of architecture and design as conflicts: stop seeing architecture as something that just solves problems, but rather be conscious that it also causes them, and discover how we can solve those problems that it’s going to cause when it becomes part of the city.

CR: Working with 20-year-olds motivates you a lot and makes you want to do things because of that transmission of energy. They are also very in touch with the latest thing, because universities continue to be sites of innovation.

What is the key to a good design for you?

CR: It’s very much about identification: understanding that it’s not just you as a designer that has to identify with the design, but rather that there will be a lot of people that will identify with it – the people living in a residence, the students at an educational centre, the people passing through a square. When the people using the design identify with it, it is very powerful. As design is a collaborative act, it continues to mutate because it passes through many hands, because there are people who build it. But to see your idea converted into something that people identify with is a very interesting emotional experience.

What makes a good designer?

RP: You must be critical of the questions that you ask yourself.

CR: It’s also a question of passion – you must really like what you do. The time, the effort, and the work that is dedicated to a design must be associated with the fact that you have passion for what you are doing. And that question of design as something very personal must be very balanced with being sensitive to the external: there must be a balance between the line of work of a studio and the collective identity of the users.

Idea, design, drafts, supervising construction…Which facet of your work do you most enjoy and why?

RP: We really enjoy creating the idea and imagining new worlds, that fiction. It’s the part that we are most able to do in a team, which is how we like to work in the studio, and how we understand architecture.

CR: And then the last part, once the design is built, to see how people use it, to make sense of all of that work, of the effort and all those phases that are sometimes more technical or tedious. It makes it all worth it.

What inspires you every day? Do you have a certain ritual, or do you consult a certain publication that is like a bible for you all?

CR: I think it’s an amalgamation of a lot of things. To design you have to have a very wide frame of reference, to know about things that are being done and that have been done. It’s also about approaching your own interests with passion and to transmit it in everything else. We all have distinct tastes, distinct interests, but somebody being passionate about a particular type of reference makes the whole team grow.

How do you all connect with what interests you? Are you more digital or analogue?

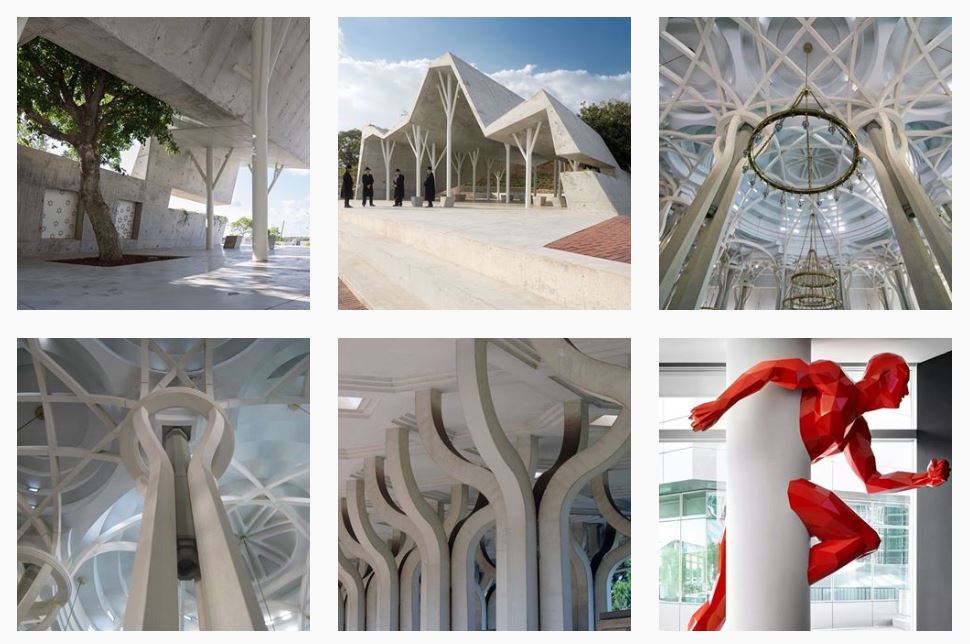

CR: Both. For example, on my Instagram where I collect bizarre columns, a big part of it is from projects that I have found in magazines, libraries etc. but I post them on a digital media platform. That hybridisation of the analogue and digital worlds really interests us when it comes to our projects too.

Who are your design inspirations and which architecture and design professional would you like to connect with?

RP: We have always been very influenced by and had a lot in common with groups that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s that were made up of radical and utopian architects, like Superstudio or Archigram. Carmelo did his thesis about this period and the idea of colectivity and reviving the idea of a city as an architectural workspace really influenced all of us. But if I had to choose an artist with whom I would love to work it would Lina Bo Bardi, who has all those collective buildings, but with a very artistic and unique approach – the buildings which have most moved me when I have visited them.