The Madrid architecture studio amid.cero9 is best known for its renovation of the Fundación Giner de los Ríos headquarters, a project that Norman Foster described as “as a wonderful breath of fresh air…inspirational.” Today we are connecting with Cristina Díaz Moreno and Efrén García Grinda to talk about architecture.

How did it feel to be complimented by Norman Foster?

CD: For an architect to compliment another architect in public is absolutely extraordinary. For an architect like him, whom we admire very much and who has done so many things, to say something good about our work is a huge payoff for all the effort we put in, because it comes from a person who understands the effort that it requires.

You’ve just come back from London, where you designed The Wooden Parliament, the project from Finsa together with the Museum of Architecture for the London Festival of Architecture. What were you hoping to achieve with it? How was it received by the public?

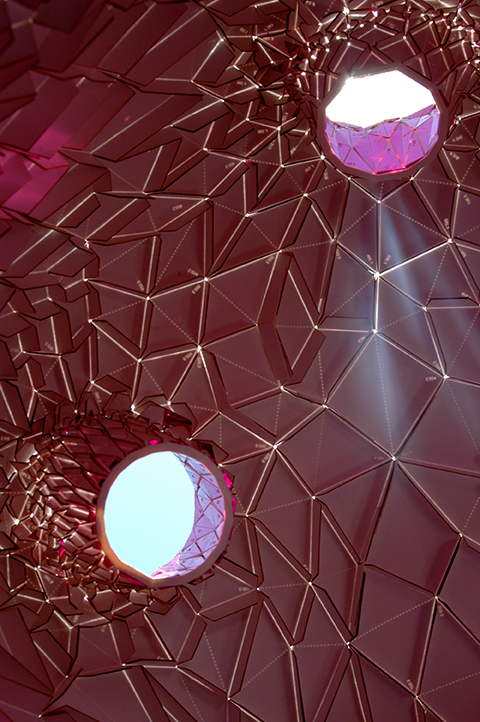

Cristina Díaz Moreno: We built a piece with very cheap materials using a very simple system. However, it uses geometry which is supposed to be a visually attractive element. And it’s working incredibly well, everyone is going to see it, taking photos and wanting to go inside. As an architect, it’s a pleasure to try to make something work in a certain way and to have it do just that.

Efrén García Grinda: It wasn’t just about it being visually attractive, but rather it was designed to be a small parliament so that people could take a moment and interact once they were inside. Its small size means it starts conversations, even if you are with total strangers, and it makes it a public piece.

Fundación Guiner de los Ríos. amid.cero9, 2014

This project fits with the philosophy of reuse and circularity, as once the LFA is over it will be moved and re-built.

EG: It is very important for us that it has a public role, that it’s not just a spectacle or appealing in some way, but rather that it serves as a place that people use and that makes them interact. It’s also important that that public role is achieved simply, with relatively cheap materials, and in a way that allows for its reuse in different places but with the same purpose. It’s something so natural that sometimes we forget about it, but we always try do this with our architecture.

CD: Sometimes what looks like complexity is confused with excess and that’s not the case at all. You can build something that has its own look using the same materials as a more anodyne piece of architecture.

Paredes Pedrosa, Moneo Brock, and Stone Designs are some of the other architectural duos that we have interviewed. It seems that in architecture creative pairs abound. What’s so good about working in a team of two?

CD: Because of the way we understand architecture, having at least two voices is essential. Despite what it has in common with art, we believe architecture isn’t exactly art, but rather a discipline that works to create spaces for people. When a person works alone, they make decisions that might end up being subjective. But if you have to deal with at least one other person, you have to rationalize your decisions and reach an agreement. I say “at least” because we understand that all the architecture work we have done over the years has been done with very big groups of people.

EF: Architecture is a type of collective art in its design, construction, or use. Very rarely can you do architectural work by yourself, for yourself, because you will always need somebody and, even if it is in the most remote place in the world, somebody is going to see it. That’s why if there are more stakeholders it will be more attuned to the people that are going to use it.

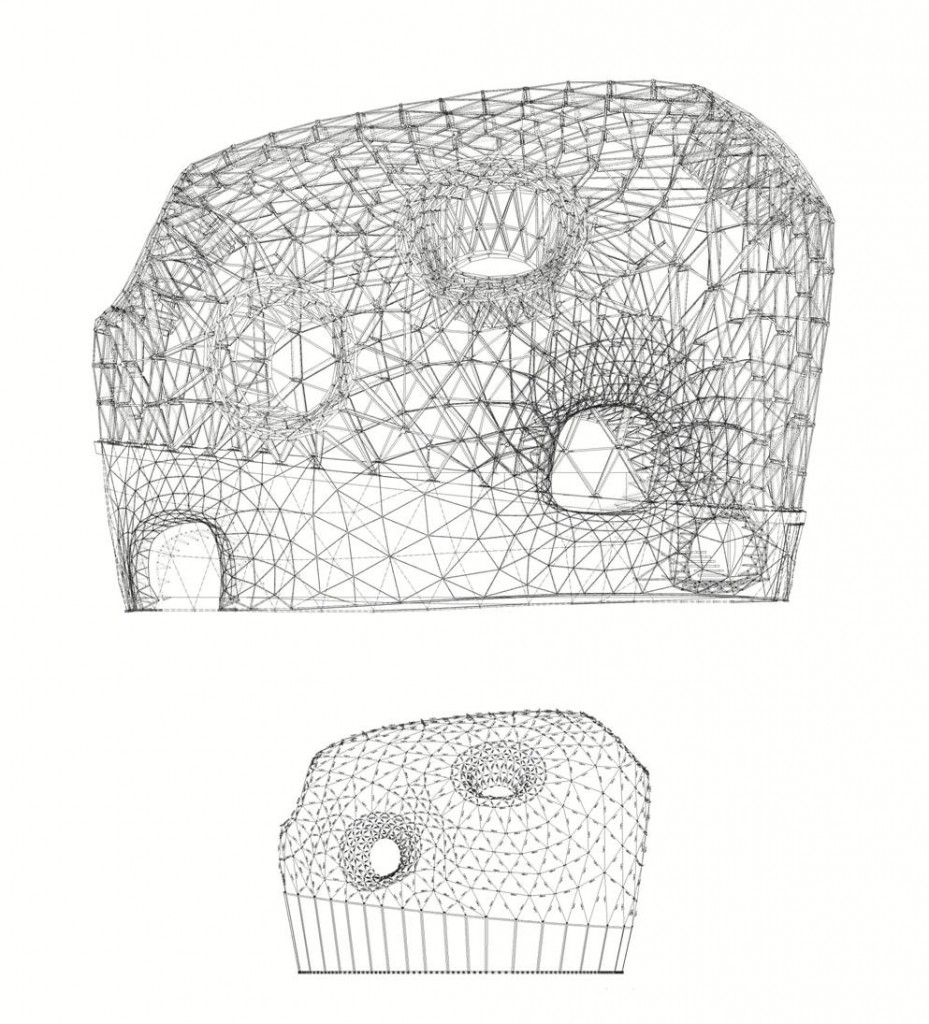

The Wooden Parliament, LFA. Amid.cero9, 2019

amid.cero9 began as a platform for collaboration. Does anything of these origins remain?

EG: The desire to try to understand as many people as possible and to involve more people in the process improves everything we do. Even if it seems like there are only two of us, in reality there are so many people involved in each thing that we do, both directly and indirectly, that it continues to be a platform for collaboration.

Your portfolio contains various projects that have not been carried out, including some prize winners. What is your relationship with these experimental projects like? Do they frustrate you or is it part of your learning as architects?

EG: There are two types of experimental projects. There are those that are designed to be made in the real world and don’t get to the construction stage due to external circumstances, which is always a little bit of a loss both for us but also for the places that they were going to be in, because architecture is for people to use, not to be looked at.

Then there is another type of internal project that isn’t meant to be realised in the real world but rather serves to develop work methodologies and to understand how we can deal with certain things in architecture so that we know how to work with them later on when we do have the opportunity to undertake projects that will be constructed. They are very speculative, but they are actually platforms for developing new tools. For example, initially we didn’t know how to work with groups of people and we set into motion a series of internal projects that were designed to prepare us with the tools to do so.

CD: We love architecture and it always frustrates us a bit when projects don’t materialise. The Wooden Parliament itself was almost built last year, and because Finsa continued to believe in the project and support us until the end, this year we made it a reality. Once it is out in the world and people interact with it, it becomes something different. It has a life that goes beyond the page.

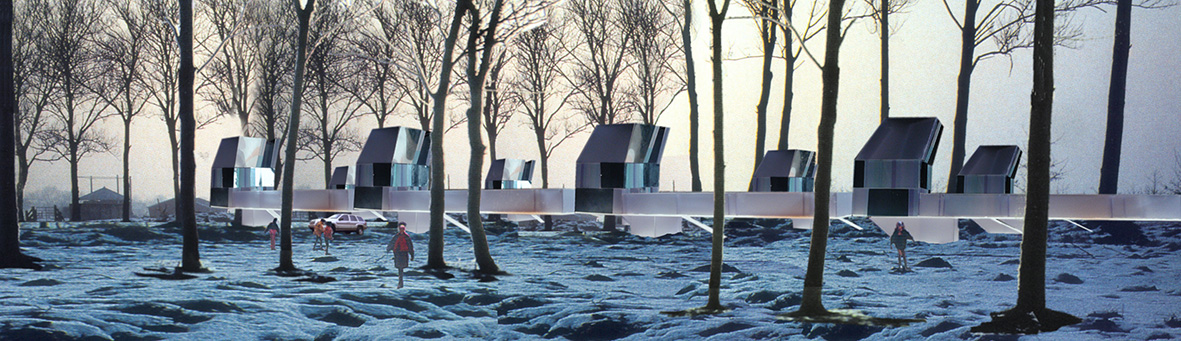

Cherry Blossom Palace, Valle del Jerte, Cáceres. amid.cero9, 2008

You engage in a wide range of teaching activities across Europe. How important is this for your architecture?

CD: Architecture is not just about technically developing a project in a studio. Rather, you have to think of architecture along various lines, and teaching and more abstract or theoretical thinking nourish the architecture that we do at the studio, just like our studio nourishes our teaching. We always say that a good architect is one that builds things and also works at a university. They don’t necessarily have to teach, but they might write or develop ideas in a more theoretical context. Doing some teaching is good for this pairing of practice and theory. Many of our former students have gone on to work with us on projects, but we also exchange interests, discoveries, projects, and more.

EG: It also allows us to stay in touch with reality. Younger generations provide us with a view of the world that is very different from our own, and we are very interested in seeing through the eyes of others because that is what architect does: they try to understand complex things that happen around us by seeing through the eyes of others.

You place a lot of importance on public spaces, as well as the relationship between architecture, its context, and people. What do you think is the main problem in contemporary cities?

EG: We must remember that cities are not only in the developed world, and so the most important problem is poverty and the instability that millions of people live with. There is another side to this, which is how to maintain the current pace of urbanisation without affecting the other necessary part of the world – nature. These are the two most serious problems being faced, not only by architecture, but also by the human condition. It’s about being intelligent enough to improve the lives of people without destroying the planet.

Is the architecture world seriously thinking about how they can contribute to the solutions to these problems?

EG: We are personally convinced of it and we try to put it into practice in our professional lives. But often these concerns are used for rhetoric or have a populist spin put on them for the benefit of those talking about them. We need to think about these topics more deeply, because there’s no going back. I don’t know if architecture can help solve them, but it can help when it comes to taking a more intelligent approach. For example, production in cities is one of the biggest sources of pollution in the world and we design them without taking into account the living conditions in large built-up urban areas.

What are you working on at the moment?

CD: We always dedicate part of our time in the studio to choosing competitions to take part in and submitting projects. Now we are also working on a project for the next Seoul Biennale, which will be unveiled in September and which is still a work in progress. We also have to organise the next stage for The Wooden Parliament, because the idea is that its appearance changes every time it changes location, so we have to design a new “outfit” for it.

Would you be able to choose a favourite from your portfolio?

EG: Your latest projects always bring a lot of pleasure, because you are still worried about the same issues. Your first projects, just like your first child, are unforgettable and remind us of what we learned, of doubts, of uncertainties. Sometimes we would like to return to our beginnings to have more time to do more things.

CD: But if we had to choose one it would be the Fundación Giner de los Ríos in Madrid, because we were lucky enough to be able to do it and it has brought us a lot of happiness. Sometimes, when we are in the garden at the Fundación with other people and they say nice things about something that we have thought up, it is very satisfying. In this case, it is not the inbred world of architecture that is acknowledging that something is good or bad, but rather people like the space without having to explain anything to anyone.

EG: That also happens at the Finsa pavilion in London. They don’t understand why they are attracted to it, it seems strange to them, but they like it. That is what we try to do: to raise awareness and tastes, to evolve in the visual world around us today.

Model of Cherry Blossom Palace at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, whose permanent collection contains various models by amid.cero9

What would be your dream project?

CD: We understand architecture for people, and rather than a dream project, we dream about a good client. A good client makes a request of you but also establishes a relationship with you so that you can work and develop the project together. It doesn’t matter if the project is big or small because it’s much better when the architecture produced is sought after and desired, not just by the architect, but also by the people who are going to use it. If we look at history, we can see that good projects often come in tandem with a good client.

Aside from the combination of professional practice and theoretical activity that you mentioned, what makes a good architect?

CD: Perhaps our ultimate ambition is to build something that is more than a series of disjointed elements or different buildings in different places all over that world that don’t make up a body of work, but rather that the work over a lifetime is really just one project in which all the parts are linked to each other. To do this, the ability to rationalize the ideas for the project and then build it, that link between what is built and what is thought up, is very important. We are seeking to build one project over a lifetime, and the architects that we respect the most and that interest us the most have done just that.

EG: It’s so difficult to define a good life. It can be defined by the wealth of experiences and knowledge and the level of harmony achieved with the world around you. I would say something similar about a good architect.

What is your work process like? Which part do you enjoy the most and why?

EG: We don’t enjoy the most monotonous part, the administrative part, very much. There are very tedious, lengthy, or enduring phases, but they are all necessary, and we enjoy them all, more or less.

What inspires you every day? Do you have a certain ritual, or do you consult a certain publication that is like a bible for you?

CD: We are inspired by the complexity and richness of the world around us. We work by first trying to understand everything related to a project that is connected to the world around it to be able to make decisions.

EG: Of course our house is full of books, architecture, CDs, things that allow us to tune into this world in an indirect way. But we understand that getting out and absorbing everything that might be of interest is more valuable. We don’t just focus on the times we are living in, we also recognise that the world has many centuries of history behind it, and we try to understand its complexity at each point in time. It’s a way of enjoying living in this world in an intellectual way.

How do you connect with what interests you? Are you more digital or analogue?

CD: We like to explore many tools and sometimes they are analogue and sometimes they are digital. We like to be able to think about things in many ways. We are also from a generation that has had to find a way to go from being analogue to digital. One part of our brains is analogue and the other is digital, which gives us many advantages because we can switch between them easily.

EG: I prefer direct contact with things, which is why I could define myself as an analogue person, but at the same time I understand and appreciate that the instruments for mediation are extremely powerful for understanding the world. I don’t just mean the digital ones, because a book, a painting, or music are all tools of mediation that allow us to see the world through the eyes and brains of other people and to have visions of it in different and conflicting ways. We are “omnivores” in the way that we approach the world.

Who are your architectural inspirations?

EG: Brunelleschi is an example, and many great anonymous engineers and builders, because we admire and respect anonymous and common construction. People that are not just receivers of a tradition, but also that discover the potential of architecture in a simple and direct way are fascinating people. They are the people that we always go back to.

CD: I would have liked to have met Rudofsky, who spent his whole life documenting architecture without architects. We like architecture and it’s not just about names. It’s also difficult to say just one name because whenever we try, the list of architects we like can reach up to 100 names.

Which architecture professional would you like to connect with?

CD: We have been lucky enough to collaborate with El Croquis since we were very young, and that has allowed us to meet lots of our contemporaries that we respect. I would say Cedric Price, who we met and who was somebody who we could do a future project with.

Three years ago, Cristina was on the panel of women at the architecture session organised by the Museum of Architecture as part of the LFA. Are these types of activities still necessary to give women in architecture visibility?

CD: They are essential. Lately there has been a huge effort to include women and to make sure they are more involved. It’s true that up until a certain time in history very few women had the opportunity to study, but now there are many generations of women working. It was necessary and it is marvellous, because it’s given visibility to a lot of interesting people. Be that as it may, if you look at history, many women have remained anonymous despite having made important contributions to architecture, and this is being improved.

EG: It’s vital, both with regards to gender and other conditions. Architecture has been a Western and masculine profession focused on the wealthy part of society. Both the creation and use of architecture must be democratised.