For several years now, ARCOmadrid, the International Contemporary Art Fair, has dedicated approximately 1,000 square meters to creating a rest area, the Guest Lounge, whose design was put out to competition so that architecture professionals could present their ideas. “It has become a rather prestigious space that has also given rise to interesting collaborations”, explains architect Manuel Bouzas (Pontevedra, 1993), one of those responsible for 350,000 Ha, the proposal presented together with the SalazarSequeroMedina studio and which has been unanimously awarded the prize. We spoke with him, with Laura Salazar-Altobelli (Lima, 1990) and Pablo Sequero (Madrid, 1989) about their participation in the contest and how they came up with the idea of focusing the conversation on the aftermath of the fires that occurred in Spain during the summer of 2025.

How did the idea of applying together for the ARCO Guest Lounge come about?

Manuel Bouzas: We are architects of roughly the same generation. We are expatriates in the United States, living between Spain and the United States, between academia and practice, and fundamentally, we work on the same scale and the same issues; we are very aligned.

Pablo Sequero: We share a generational interest in rethinking the materials we work with and a clear joint interest in research with wood.

Laura Salazar-Altobelli: We also share an academic background, which is what drives our work to always be more focused on research. There is an intellectual project behind every project we undertake.

How did the entire process unfold, from the initial proposal submission?

Manuel Bouzas: It’s not a typical competition where you make a graphic proposal and the coolest building or project wins. You start with a letter explaining why you would like to do it, like a love letter. The theme that ARCO articulated this year was that of “two spaces within the fair”, and it seemed ambiguous enough to us to present ideas that reflected on one space and the other, so we considered what would happen if one of those places was not at the fair.

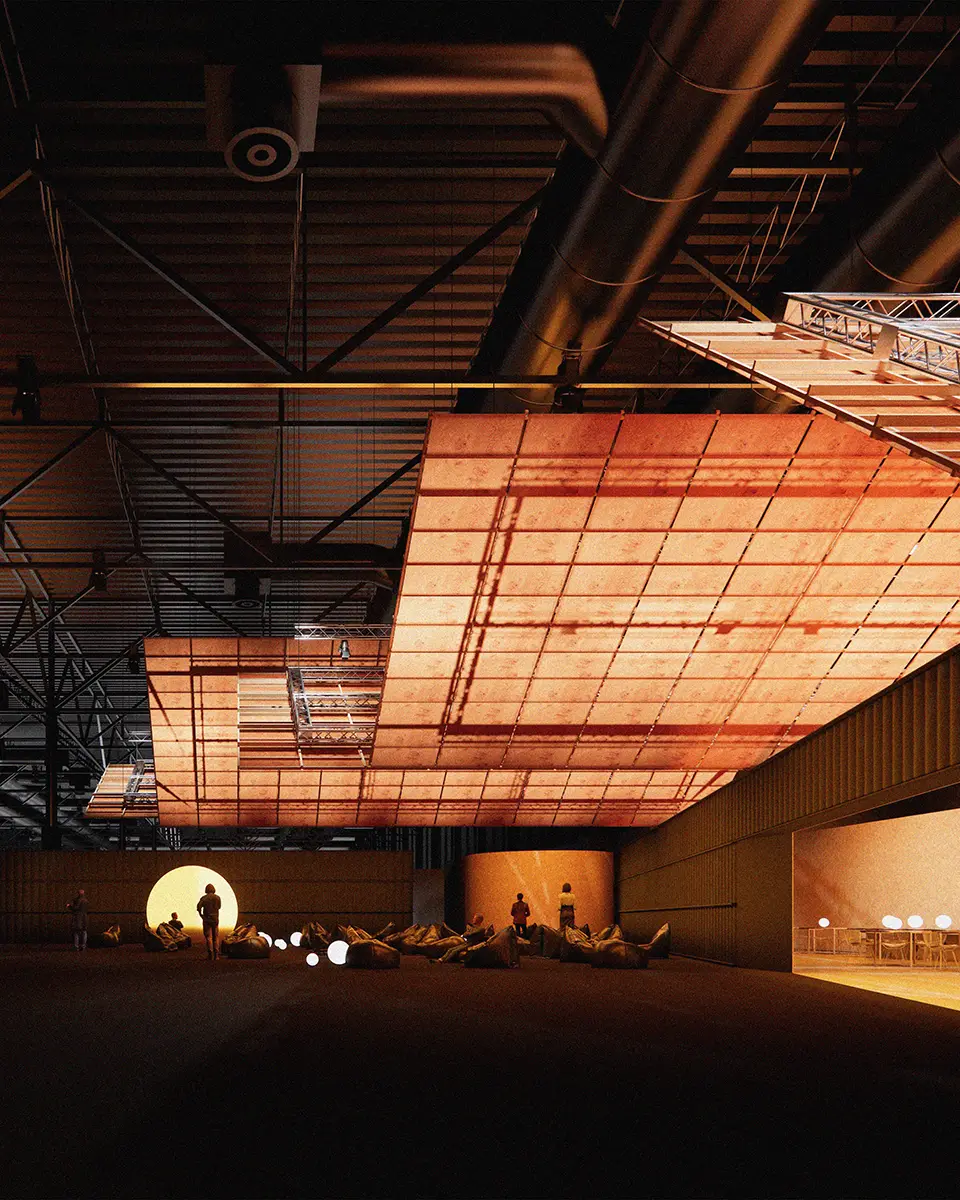

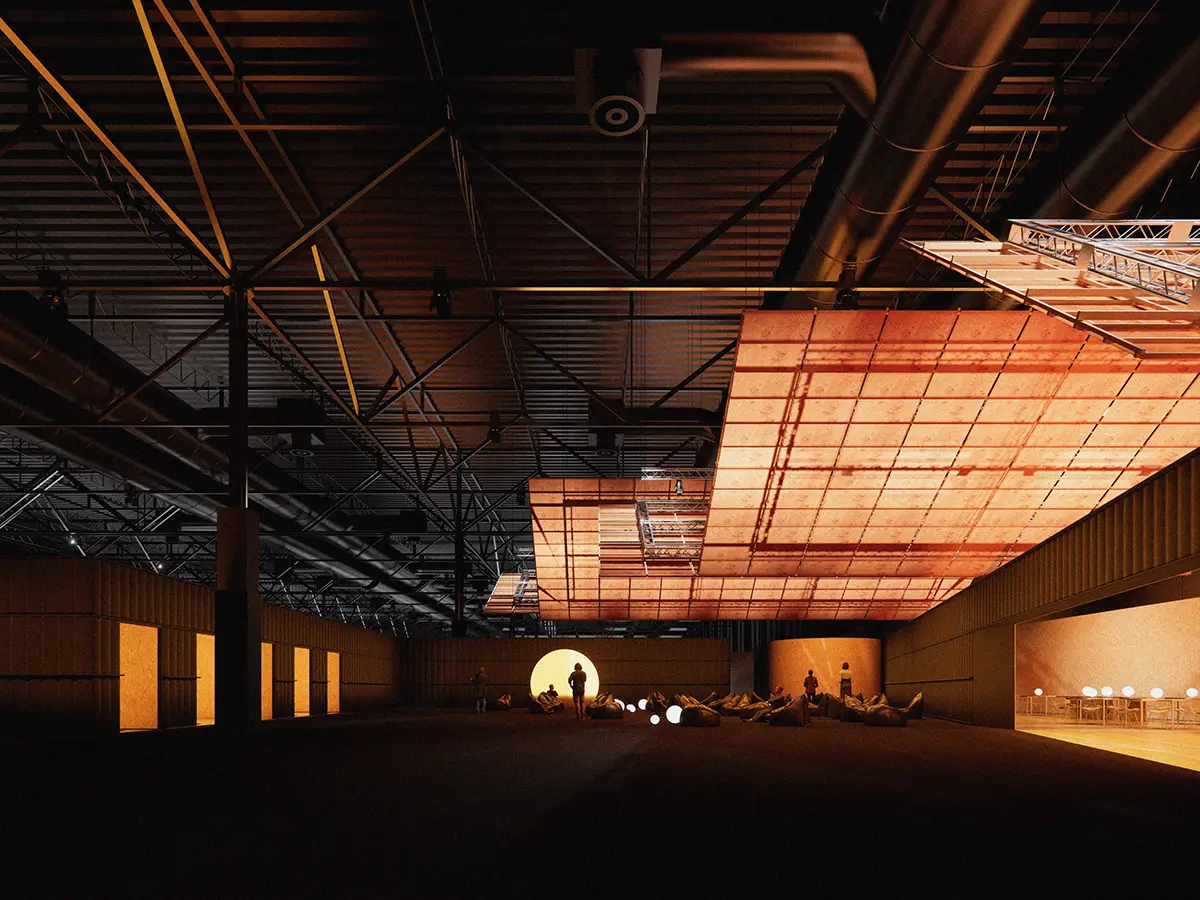

One would be the interior, the one we built, the Guest Lounge, but the other could be outside. This opened up the possibility of launching a message in a forum as international and powerful as ARCO on a cultural level. We wanted to shed light on a topic that gains exposure for a couple of weeks a year, but which we all then forget about: the fires of August 2025, which burned the 350,000 hectares that give the project its title. In the letter we already raised the other issue: what happens if we work with the waste or the material affected by those fires?

They selected three proposals to present a graphic document and from there, we started working: we already spoke with Xosé Mera from Veta Forestal, with the whole team at Finsa, and we further shaped the content. We wanted to generate a reflection on how companies in the sector and we as designers can work with the reaction to a disaster and shift the focus. We always talk about prevention, but we need to talk about reaction: how the Arume Foundation preserved timber prices, or how Veta allocated resources, machinery and people who were working in Zamora to address this.

The issue of reusing burned materials, the result of a tragedy, is a delicate matter. How did you find the balance so that it doesn’t look like you’re profiting from the devastation?

Pablo Sequero: It’s about observing a traumatic event and trying to make it visible and make it a present conversation, not only in the summer months, but something transversal. We generated what we called in the competition a material palette in which different ways of recovering the wood from those burnt logs could be explored. We are also interested in mixing this with the almost atavistic idea of fire as an element that has always brought people together around it, what we used to call the hearth. But we wanted to be very tactful and respectful, generating visibility around this conversation.

Manuel Bouzas: One detail that is not usually highlighted is that it is necessary to remove all the burnt wood before March, because after six months, a series of diseases are generated that can contaminate the soil. This creates pressure to salvage wood that many people believe is damaged, but which actually still has value. On the other hand, with this, we effectively contribute visibility: reports that have already been published, journalists and photographers who have gone to Laza to see those mountains, and the fact that the conversation will be taking place at one of the most important art and culture fairs in Europe.

In addition, we have the people from those mountains: Rosa, the president of the Community of Mountains, has explained why it is important to talk about these issues, what they are going to do with the recovery of the wood, thanking the Arume Foundation for preserving the prices, because thanks to that they are going to build the social centre that they had lost. This brings to the forefront a lot of issues that put the focus back on the reaction.

Laura Salazar-Altobelli: It’s a project that has many scales. Globally, climate change is affecting everyone in the world, and these fires, which are tragic in the summer, are part of an even larger movement. Then we come to the material scale, which has to do with these specific forests: the participation of all the people involved in removing that wood, with us as architects in a very small part, recovering a fragment of that material for this installation and turning it into something that is even more ephemeral and intangible. It is an experience in which one can enjoy the space and, at the same time, remember and reflect on everything that has happened to get to that moment.

What message were you interested in conveying from an architectural point of view?

Pablo Sequero: We want it to be an evocative space, that atmosphere of the fire, and that also serves at different scales. Both for a very intimate experience through the way we work with light, with colours, with the material palette, and at the same time as an almost monumental environment for a large gathering.

Manuel Bouzas: It also has to do with how architects and people who work with space, territory and urban planning know that the decisions we make mean many things. It is no longer a question of the budget it costs to make a square meter or whether it is more beautiful or uglier, whether it is curved or straight, but we know that there is an ecological implication and an environmental footprint in every material decision we make.

Ultimately, architecture consists of moving resources from one place to another, deconstructing one place to build another. If we pay a little more attention to where those resources come from, what implications they have, we are actually contributing in some way to introducing some ecological thinking into design. It is something that had not been given attention for practically the entire history of architecture and that in recent decades has gained more importance because we know that we consume 40% of global emissions.

What did you all learn during these months of work?

Laura Salazar-Altobelli: Pablo and I are not from Galicia, and we had the opportunity to travel to the forests, see them firsthand, and meet the people who work on them every day. We have learned a lot about everything: seeing the material itself, visiting the lumberyards, the sawmills that show us exactly where each log passes through, what the machinery is, and what the peeling or cutting process is like.

Manuel Bouzas: As a main lesson, I would mention how nice it is sometimes not to do the work alone and to share it with other people. Making decisions among several voices and dismantling the idea that design is a single person in a room listening to classical music and painting with charcoal.

Actually, it has to do with limits, with the inherent contradictions of the process, with talking to a forester, or someone from a sawmill or logistics who tells you what can and cannot be done. Ultimately, design lies in reconciling all these issues and trying to find the lowest common denominator that, even so, maintains an idea as beautiful. It is a constant learning process every time we challenge the standard conventions of the materials we use and how we use them. For example, trying to convince a sawmill in Celanova, in Ourense, that the log he was going to shred, because he believes it has no value, will become an ornamental piece at the most important art fair in Europe.

Pablo Sequero: There is also the material exploration or laboratory component. We’ve thought about what happens if those coastal surfaces with the burnt wood texture are applied, for example, to a wall. Suddenly, you have a facade with that burnt wood texture that really makes you see the effects of the fires, but also conveys a weight. Or take something like the veneer, those covers used for boards, and say: “What if we just keep one?” What happens if we shine a light on it?”

Manuel Bouzas: Regarding this, it has surprised even at Finsa itself that this 0.4 mm sheet, which is usually used for finishing boards or plywood, is also incredible if you put a light behind it. Suddenly, it transforms into a lamp. It’s just a thought that there are a lot of things that we don’t value in an industrial process, and when you take them out of context, suddenly they do have value.

Where do you find inspiration to materialise proposals like ARCOmadrid?

Manuel Bouzas: I find Galicia as a very inspiring region. I am inspired by the people who are there, I am inspired by those forests, those mountains, what happens to them, I am inspired by the granite quarries, I am inspired by the productive landscapes, I am inspired by the coast. All the work I do in terms of research, design, etc., is always somehow linked to a territory that I find fascinating because of the number of stories it has. I am inspired when people can extract the beauty that exists in their places, because not everything is about big cities, as it sometimes seems in the 21st century. The people who work to publicise these places and get the most out of these small economies, of those things that we think have no value, personally inspire me.

Pablo Sequero: For me, there is something very good and very beautiful generational, which is to make a virtue of scarcity. Where resources may be lacking, we can pool what we have and reach more places at once. That climate of scarcity, in which many of us have studied and begun to practice, has changed the way we seek inspiration and the way we observe. Observe, learn to pay attention to things that may have to do with material things, with regional things.

Laura Salazar-Altobelli: We architects have a proclivity towards beauty, towards seeking beauty through design, and I have always wondered, as an architect, how you can combine that with making a positive change when so many things seem to be against you: the contribution of the construction industry to carbon emissions, the role of the architect in different economic and political systems… How to make a change for the better? I believe that as a generation and as architects, we are always looking for this way of working in environments of scarcity with material that may lend itself to reuse. We are forging our own path and finding our own answers to that same question. But always, hopefully, doing something that is inspiring in itself and that is beautiful.